Valley Patriot of the Month

CONCORD/ANDOVER – Tom Hudner was sitting in the commons area after lunch at Phillips Academy in Andover when word spread that the Japanese had just bombed Pearl Harbor. As with most young people of the era, he had no idea where Pearl Harbor was but he knew it meant the U.S. was at war. And like many of the students in the Class of ’43, Tom expected to become part of the war effort after graduation. But fate would take him to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis where he would not graduate until 1946, well after the conclusion of World War II.

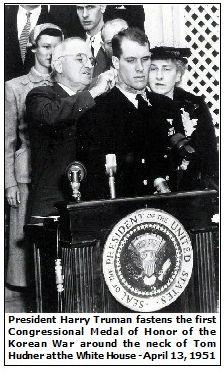

Four years after Annapolis, however, Tom would find himself in another war, the Korean War. Here he would lead a heroic effort to save a downed pilot when his flight was on patrol over the Chosin Reservoir. For this extraordinary rescue attempt, President Harry Truman would present the first Congressional Medal of Honor of the Korean War to Tom Hudner.

Born in 1924, Tom grew up in Fall River, Mass. where the family had a chain of meat and grocery stores called Hudner’s Markets. His father and uncle had attended Phillips Academy and later he and his brothers would do so as well. While at Phillips, Tom was co-captain of the track team, a member of the football and lacrosse teams, a senior class officer and student council member. These endeavors would later help prepare him well for the responsibilities of a military career.

Tom’s father had attended Harvard after Phillips, but Tom had always thought about going to Annapolis and subsequently into the Navy. In 1943, Congressman Joe Martin, then Speaker of the House of Representatives, appointed Tom as his second alternate to the U.S. Naval Academy. As luck would have it, a position opened up and Tom was told to report to Annapolis on July 7, 1943.

During the next few years Tom would train to be a naval officer. His ultimate goal was to be stationed aboard a destroyer or battleship. In 1946 Tom graduated from the Academy and now Ensign Thomas Hudner was assigned to the cruiser USS Helena. That September, Tom became a communications watch officer on the Helena stationed off of Tsing-Tao, China, about 150 miles north of Shanghai. Although the Nationalists were still in control of China, the communists and Red Army were making it increasingly difficult for Americans. It was Tom’s duty to read incoming and outgoing messages, decode/encode them, and pass them along to interested officials.

During the next few years Tom would train to be a naval officer. His ultimate goal was to be stationed aboard a destroyer or battleship. In 1946 Tom graduated from the Academy and now Ensign Thomas Hudner was assigned to the cruiser USS Helena. That September, Tom became a communications watch officer on the Helena stationed off of Tsing-Tao, China, about 150 miles north of Shanghai. Although the Nationalists were still in control of China, the communists and Red Army were making it increasingly difficult for Americans. It was Tom’s duty to read incoming and outgoing messages, decode/encode them, and pass them along to interested officials.

After six or seven months on the ship, the Helena sailed back to Long Beach, California. There, Tom received new orders to report to Pearl Harbor as a communications officer. Unhappy at his new post because he was not at sea, several classmates serving with him eventually convinced him to put in a request for flight training. Tom was accepted and in April 1948 reported to Pensacola Naval Air Station in Florida for flight school. He learned to fly in the North American SNJ, the naval equivalent of the Air Force T-6 trainer. He had to complete six successful, arrestor-hook carrier landings to graduate.

Then it was on to Corpus Christi, Texas for advanced training with the Corsair F4U and finally back to Pensacola where he received his aviator wings in August of 1949. His first duty was at the Naval Air Station at Quonset Point, Rhode Island where he was assigned to VA-75, an attack squadron of Douglas AD-1 Skyraiders, as part of Air Group 7. About a month later, VA-75 was decommissioned and he was reassigned to VF-32, a Corsair squadron aboard the USS Leyte aircraft carrier. On May 1, 1950 the Leyte sailed to the Mediterranean for a six-month deployment.

Tom was now Lt. j.g. Tom Hudner.

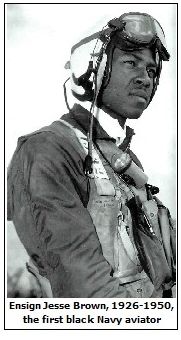

It was at Quonset Point where Tom would first meet Ensign Jesse Brown, another aviator assigned to the same squadron. Ensign Brown was the Navy’s first black aviator. Although the Tuskegee Airmen had paved the way for black aviators in World War II, it still took years for the other services to accept this cultural change.

It was at Quonset Point where Tom would first meet Ensign Jesse Brown, another aviator assigned to the same squadron. Ensign Brown was the Navy’s first black aviator. Although the Tuskegee Airmen had paved the way for black aviators in World War II, it still took years for the other services to accept this cultural change.

Brown had grown up in Mississippi, was valedictorian at his high school, and attended Ohio State University. While at Ohio State, a naval officer encouraged him to apply to the Navy’s flight school. Jesse had always wanted to fly, so this became his goal. He eventually went through the same training as Tom Hudner, first at Pensacola and then Corpus Christi. Tom believes Jesse was eventually assigned to Quonset Point to get him away from the bigotry that was still widespread in the South.

The USS Leyte was off the coast of Cannes, France, about a month and a half into its deployment, when North Korea attacked South Korea. Like Pearl Harbor, the first question on most people’s minds was “Where is Korea?” On August 8th, five to six weeks after the initial attack, and after being relieved by another carrier stationed off Lebanon, the Leyte was ordered to Korea.

The first port of call was back to Norfolk for war preparation and to take on six Marine Sikorsky helicopters and ten Marine pilots. The USS Leyte left Norfolk and after traversing the Panama Canal headed west into the Pacific. She dropped off the Marines and their helicopters in Japan and then arrived off the east coast of Korea on 8 October 1950. The Leyte joined with three other carriers to provide close ground support to U.S. troops ordered in that summer by President Truman.

The Leyte at this point had one squadron of Grumman F9F-2 Panther jets, two squadrons of Chance Vought Corsair F4U-4 fighters, and one squadron of Douglas AD-1 Skyraiders. The jets were the superior fighters, but they could only stay in the air half as long as the other aircraft. Thus, close ground support missions were generally left to the Corsairs and Skyraiders.

Flight operations started immediately and consisted of 12-hour days where Tom, Jesse and the other pilots would fly one, sometimes two, missions a day, standing down every fourth day for replenishment and refueling. Every one-and-a-half hours the carrier was launching or recovering aircraft. Early on, one of the Leyte pilots brought back word that the Chinese appeared to be entering the war.

When hoards of Chinese troops suddenly appeared everywhere on November 28th, all hell broke loose. Air operations then shifted to protecting the retreating American troops, now well north of the 38th Parallel.

On December 4, 1950, Tom Hudner, Jesse Brown and four other Corsair pilots left the USS Leyte at about 1330 hours to fly an armed reconnaissance mission over the northwestern part of the Chosin Reservoir, a mountainous, snow-covered, inhospitable area about 70 miles from the Chinese border. They were flying low, only 500-700 feet above the terrain, looking for enemy targets of opportunity.

On December 4, 1950, Tom Hudner, Jesse Brown and four other Corsair pilots left the USS Leyte at about 1330 hours to fly an armed reconnaissance mission over the northwestern part of the Chosin Reservoir, a mountainous, snow-covered, inhospitable area about 70 miles from the Chinese border. They were flying low, only 500-700 feet above the terrain, looking for enemy targets of opportunity.

Suddenly, Jesse radioed that he was losing oil pressure and power. He would have to land. Another pilot noticed a small clearing only about a quarter mile in size on the side of one of the slopes and radioed the location to Jesse. Tom also radioed to him, “Jesse, make sure your shoulder harness is locked and the canopy is open!” Then Jesse, wheels up with no power, brought his Corsair in for a hard, crash landing. The impact buckled the fuselage at the cockpit.

Other flight members who were circling the area at the time first thought he had been killed because of the force of the impact. The flight leader had even started climbing to a higher altitude so he could radio for a helicopter to come in and retrieve the body. But then some of the pilots could see Jesse waving from the damaged craft. He was still alive although he didn’t appear able to get out of the aircraft. There was also smoke coming from the cowling, an ominous sign.

It was obvious that Jesse was trapped and, with the imminent threat of a fuel fire, he needed immediate help to survive. The helicopter wouldn’t arrive in time to do any good. Then Tom Hudner radioed the rest of his formation, “I’m going in to get him out!” He says there was silence on the radio after that. No one tried to talk him out of it.

Then he turned towards a nearby hillside and fired off all his rockets and ammunition to both lighten the plane and reduce the hazards of a crash landing. Looking for how best to land, he slowed to about 85 knots and maneuvered the Corsair into an area near Jesse on a slope of about 20 degrees. Wheels up, he landed hard about 100 yards from Jesse’s Corsair. The snow didn’t help the impact at all, as the ground below was frozen solid. The crash landing broke his windscreen and injured his back. Tom later said, “That was the hardest landing I ever made.”

With adrenaline pumping, Tom ran through the snow to Jesse’s plane. It was cold, perhaps no more than 5 or 10 degrees. He didn’t see any enemy soldiers, but wasconfident that his air cover, now increased to 10-12 planes, would keep them away. When he reached Jesse, he saw that he had his helmet off and his gloves were missing. Tom surmised that Jesse had taken the gloves off to unbuckle his chute and dropped them. Tom then put a woolen watch hat on Jesse and wrapped his hands in a scarf that he had brought with him. Jesse was obviously badly injured.

A quick glance showed that Jesse’s knee was pinned between the bent fuselage and the central instrument column. The snow made it slippery and Tom struggled to maintain his footing as he leveraged himself to free Jesse. It didn’t take him long to realize that he would need some kind of tool to help. Tom returned to his plane and radioed his flight leader to have the helicopter bring an ax and fire extinguisher. Then he returned to Jesse’s plane to consider what else he could do. He started packing snow into the cowling openings to suppress the smoldering fire. At this point, Jesse was fading in and out of consciousness from the injuries and the cold.

A quick glance showed that Jesse’s knee was pinned between the bent fuselage and the central instrument column. The snow made it slippery and Tom struggled to maintain his footing as he leveraged himself to free Jesse. It didn’t take him long to realize that he would need some kind of tool to help. Tom returned to his plane and radioed his flight leader to have the helicopter bring an ax and fire extinguisher. Then he returned to Jesse’s plane to consider what else he could do. He started packing snow into the cowling openings to suppress the smoldering fire. At this point, Jesse was fading in and out of consciousness from the injuries and the cold.

Meanwhile, the helicopter which had been launched from a nearby Marine camp was already in the air when it got word that that there were two pilots on the ground and they needed an ax and fire extinguisher. The news meant that the chopper had to return to base and drop off the crewman that the pilot had taken with him and pick up the requested items. Finally, in what seemed like forever, the helicopter arrived over the crash scene.

As it circled the area, Tom fired a flare/smoke emitter to show the pilot how the wind was blowing. But the helicopter took its time landing because, as Tom later learned, the brakes on the chopper were poor and the pilot was afraid that if he landed on a slope the helicopter might slide off the hill. Also, the engine on this chopper had a history of trouble starting so the pilot would have to leave it running.

The Sikorsky finally landed and out stepped 1st Lt. Charlie Ward. Instantly, Tom recognized him as one of the Marine pilots the Leyte had ferried to Japan several months earlier. The two then hurried over to Jesse to try to free him. But the ax was ineffective on the metal fuselage no matter what they did. Try as they might, they could not get Jesse out of the aircraft. At one point when Jesse was conscious, he told Tom, “If anything happens to me, tell my wife Daisy I love her.”

It was now getting late in the day and Ward turned to Tom and said, “We have to leave. I can’t fly out of these mountains in the dark.” Tom reluctantly agreed. He then turned to Jesse and told him they had to leave to get some equipment. He knew, however, that there was no chance they could get back before morning and Jesse wouldn’t survive the night.

Charlie and Tom then boarded the chopper and flew south to the Marine base camp at Hagaru-ri. It was cold and Tom would have to spend the night in a tent. A young Marine appeared and gave Tom his bedroll. He said, “Sir, tonight I think you will need this more than me.” Tom says he didn’t sleep at all because of the cold and his thoughts of Jesse.

The next morning, December 5th, Tom was flown to another Marine base at Yonpo where he would spend the next two days because of bad weather. Finally, on December 7th a Skyraider from the Leyte came in to take him back to his ship. On the way to the carrier, Tom learned that the captain wanted to see him as soon as he came on board. Radio communication had been poor over the past several days and Captain Thomas Sisson had little information on what actually happened.

After listening to Tom’s story, Capt. Sisson said he would send in a helicopter with a flight surgeon to retrieve Jesse’s body. Tom advised him that would be too dangerous and needlessly risk the lives of two more men. The captain then said he had a backup plan. He would send in planes with napalm to incinerate the crash area – a makeshift warrior’s funeral. Within the hour, seven aircraft from Squadron 32, all flown by Jesse’s friends, left the carrier for the crash site. Six carried napalm and while they were diving to drop their ordinance, the lone seventh plane climbed above them in the traditional tribute to a fallen comrade.

After the mission had been completed, Capt. Sisson started the process recommending Tom for the Medal of Honor. Meanwhile, Tom’s injured back now started to really bother him and he was grounded for the next month while recovering. Shortly after he returned to flight operations, the USS Leyte got orders to head back to San Francisco. In mid-February, VF-32 returned to Quonset Point.

On April 1st Tom got word that the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Congress had approved him for the Medal of Honor. On Friday, April 13, 1951, President Truman presented the medal to Tom in a White House ceremony before family and friends.

Tom would also find out later that Charlie Ward, the Marine helicopter pilot, received the Silver Star for his heroic efforts on that day. Jesse Brown was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his Korean War combat service.

Tom now settled in as a career Navy aviator. He spent time as an instrument instructor, admiral’s aide, assistant air officer, executive officer of an aircraft carrier, exchange pilot flying Air Force interceptors, and finally a tour with the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon before retiring in April 1973 with the rank of captain.

Tom returned to Massachusetts and over the years worked for several Boston area companies in various consulting, management and administrative capacities. In 1988 Governor Dukakis appointed him to Deputy Commissioner of Veterans Services. He eventually became Acting Commissioner and in 1991 Governor Weld appointed him to Com-missioner, where he remained until retirement in 1999. Tom is currently vice president of Battleship Cove, the USS Massachusetts war memorial and museum complex in Fall River.

In 1963, while undergoing jet training in San Diego, Tom met the recently widowed Georgea Smith at a Christmas party. They started dating and were married in August of 1968. The Hudners have a son, Tom, who lives in Concord. Georgea has three children from her prior marriage: Kelly, Stan and Shannon. Between them, the Hudners have 11 grandchildren.

Captain Thomas J. Hudner, Jr., we thank you for your extraordinary service to our country.

To nominate a local veteran to be honored as a Valley Patriot of teh Month you can email us at valleypatriot@aol.com