Brad MacDougall-Congressional Aide to Rep. Marty Meehan and Kathleen Corey Rahme

By: Ted Tripp – May, 2006

METHUEN – As 85-year-old Luther McIlwain slowly walks around the kitchen table in his Pleasant Valley home, it is obvious that this Tuskegee Airman has a lot more story to tell about his military experience during World War II. Each little parcel of information he shares tells us about an era where Negroes were second class citizens that worked and fought hard to show that they were the equals of white soldiers and officers.

They had to prove to the military that they had the skills and knowledge to fly sophisticated aircraft in life-and-death combat situations.

Today we know they performed superbly with some of the best records of the war. In last month’s The Valley Patriot, we followed Luther McIlwain’s early life and the discrimination problems he endured simply trying to enlist in the Army’s new Tuskegee program designed to train Negro pilots, bombardiers and navigators.

We pick up the story when, after a brief period at Ft Bragg, N.C., Luther was transferred in January of 1944 to Keesler Army Airfield at Biloxi, Miss. to become part of the 1120th training squadron. He was now a preaviation cadet undergoing three months of physical training, testing and evaluation in preparation for Tuskegee. Out of more than 400 original applicants, only 44 passed the rigorous program to go on to the next step. It was also here that Luther was assigned to be a bombardier/navigator rather than a fighter or bomber pilot, since that’s where the Army needed men at the time. You had no choice in those days.

In April or May, Luther was sent to Tuskegee as a full-fledged Army Air Corps cadet. He had a propeller emblem on the front of his cadet cap and another one on the sleeve of his uniform. The first step was ground school, which consisted of 12-hour days studying aerodynamics, physics, radio transmission, Morse code, English and other related subjects. At this time there were 8000 to 9000 Negroes training at Tuskegee under white officers. By 1944 the Army had managed to replace the original white ground school instructors with qualified Negro instructors. As more Negroes were trained and promoted, they would eventually replace all of the white officers. Near the end of the war, only the base commander and his immediate staff were white.

In April or May, Luther was sent to Tuskegee as a full-fledged Army Air Corps cadet. He had a propeller emblem on the front of his cadet cap and another one on the sleeve of his uniform. The first step was ground school, which consisted of 12-hour days studying aerodynamics, physics, radio transmission, Morse code, English and other related subjects. At this time there were 8000 to 9000 Negroes training at Tuskegee under white officers. By 1944 the Army had managed to replace the original white ground school instructors with qualified Negro instructors. As more Negroes were trained and promoted, they would eventually replace all of the white officers. Near the end of the war, only the base commander and his immediate staff were white.

Just 27 of Luther McIlwain’s class of 44 graduated from ground school. They were then sent to Hondo Army Air Field near San Antonio, Texas for bomber navigation training. Here, Luther earned his navigator wings and was promoted to 2nd lieutenant. He also became a Rated Instructor. His graduation class was only the second of Negro cadets to be trained as bombardiers/navigators. Now his final class size was down to just 23 elite Air Corps soldiers.

From here it was on to San Angelo Army Air Field in Texas for bombardier training with the famous Norden bombsight. After a month of ground school, followed by simulator experience, Luther McIlwain honed his skills in twin-engine B-25 bomber trainers. At 22 years of age, he earned his second set of wings – the bombardier wings – and was making 50 percent more money than the equivalent non-flying officer.

From here it was on to San Angelo Army Air Field in Texas for bombardier training with the famous Norden bombsight. After a month of ground school, followed by simulator experience, Luther McIlwain honed his skills in twin-engine B-25 bomber trainers. At 22 years of age, he earned his second set of wings – the bombardier wings – and was making 50 percent more money than the equivalent non-flying officer.

By now it was mid 1944 and Luther’s next stop was the University of Chicago’s School of Meteorology for three months of weather instruction. He graduated as a Rated Weather Observer, the first and only Negro airman in a class of 200 other white officers. Then, after a brief return to Tuskegee, Luther was assigned to the Tyndall Army Air Base at Panama City, Fla. Here he practiced firing .30- and .50-caliber aerial guns from B-17s and B-24s at targets towed by nearby aircraft. After Tyndall, Luther’s career took an unusual twist. He was sent to Midland Army Air Base, Texas for three months where he was one of only four Negro instructors assigned to help train the first group of Chinese flying officers from Chiang Kai-shek’s army. At the time, the Chinese Nationalists were fighting both the Japanese army and the threat of an internal Communist takeover.

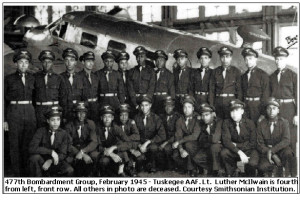

It was now early 1945 and Luther’s next assignment was to Godman Army Air Field at Ft. Knox, Ky., where the all-Negro 477th (C) B-25 Bomber Group was being assembled. The Army was still wrestling with discrimination at this time, as the (C) designation was used to denote “colored.” Luther McIlwain was given orders to become part of the group’s 617th squadron.

It was now early 1945 and Luther’s next assignment was to Godman Army Air Field at Ft. Knox, Ky., where the all-Negro 477th (C) B-25 Bomber Group was being assembled. The Army was still wrestling with discrimination at this time, as the (C) designation was used to denote “colored.” Luther McIlwain was given orders to become part of the group’s 617th squadron.

From Godman, the 477th was sent to the much larger Lockbourne Army Air Base near Columbus, Ohio and became a composite group of bombers and fighters. Here, Luther McIlwain was given orders to return to Tuskegee for pilot training on twin-engine planes. He had accumulated 80 hours of flight instruction — just 10 hours short of what he needed for his pilot’s wings — before the program was abruptly terminated. By now, Germany had already surrendered and the Japanese were only weeks away from surrender. The Army didn’t need any more bomber pilots; they had a surplus. Although Luther had spent countless hours in the air as a navigator and bombardier, he never did qualify for his pilot’s wings.

The 477th Bomber Group did not see combat during the war, primarily because its white commander, Colonel Robert Selway, as well as Major General Frank Hunter, were so bigoted that they did almost everything they could to sabotage the training of the unit. Their treatment of the Negro officers broke Army regulations and was so outrageous that 101 of the Negro officers mutinied and were arrested for refusing to stay out of a newly created “White Officers’ Club.” After the war ended, Luther stayed in the service until the end of 1946.

The 477th Bomber Group did not see combat during the war, primarily because its white commander, Colonel Robert Selway, as well as Major General Frank Hunter, were so bigoted that they did almost everything they could to sabotage the training of the unit. Their treatment of the Negro officers broke Army regulations and was so outrageous that 101 of the Negro officers mutinied and were arrested for refusing to stay out of a newly created “White Officers’ Club.” After the war ended, Luther stayed in the service until the end of 1946.

During the post war period, he was privileged to be the lead navigator in a group of 21 B-25 Bombers escorting General Jonathan Wainwright (captured by the Japanese at Corregidor in 1942) from Texas to Ohio for a special ceremony. Also, in 1946, Luther McIlwain and his crew took first place in precision bombing at an air show competition where 50 bomber squadrons were selected from various air bases around the country to compete in combat-style maneuvers. Upon completion of his military service, Luther McIlwain decided to become a police officer in New York City after the police force was finally integrated in 1946. He spent 20 years there, the last 13 as a plainclothes detective.

It was during this time, unfortunately, that all of Luther’s pictures, patches, wings and other military memories as a Tuskegee Airman were stolen from his apartment. All he has left today is his old military ID and a fuzzy picture of him as a cadet that he had sent to his mother. Eventually, Luther made it back to Methuen where he worked for over 20 years as a special assistant to the mayor in the Office of Equal Opportunity. He officially retired in 1992. But Luther McIlwain wasn’t through yet. In 1998, at the age of 77, he received a phone call from Harvard University to talk about his

It was during this time, unfortunately, that all of Luther’s pictures, patches, wings and other military memories as a Tuskegee Airman were stolen from his apartment. All he has left today is his old military ID and a fuzzy picture of him as a cadet that he had sent to his mother. Eventually, Luther made it back to Methuen where he worked for over 20 years as a special assistant to the mayor in the Office of Equal Opportunity. He officially retired in 1992. But Luther McIlwain wasn’t through yet. In 1998, at the age of 77, he received a phone call from Harvard University to talk about his

Tuskegee experience in its Division of Continuing Education. For two years this Tuskegee Airman taught to overflowing crowds of retired doctors, professors, and company presidents. Not surprisingly, Luther has also been the recipient of numerous awards. In 1996, the Massachusetts Black Legislative Caucus presented him with a pewter cup and its Public Service Award. In 1997, the Merrimack Valley Chapter of the NAACP also gave him its Public Service Award. In 1999, Hanscom Air Force Base presented him with a “Lifetime Honorary Membership” in the Hanscom Officer’s Club. Also in 1999, the Merrimack Valley Planning Commission, on which Luther had served for 13 years, gave him its Regional Service Award. And this past February the Boston Celtics presented him with a “Heroes Among Us” award prior to a game with Cleveland at the Boston Garden.

As an aside, it should come as no surprise that Luther’s younger sister, Glendora, also excelled in her career. She became a lawyer in 1951 like their father and would go on to serve as an Assistant Secretary of HUD in President Ford’s administration. For many years she was also active on transition teams for newly elected Republican governors here in Massachusetts, including Governor Weld’s 1990 move into the gubernatorial office.

At this point in the story about “Hero in Our Midst,” it is traditional for this paper to thank the veteran for his service. Somehow, for Luther McIlwain this seems woefully inadequate. He not only served his country well, he helped lead the way by example for the subsequent integration of the Armed Forces after the war and the groundbreaking 1964 Civil Rights Act. This has all led to a much better America in which we live today. So, we will say simply and with great admiration, “Thank you, Luther McIlwain, for all that you and your family have done to make this a better country and us, a better people.”