Valley Patriot of the Month

PART 2

By: By Ted Tripp April, 2007

By: By Ted Tripp April, 2007

(read part 1)

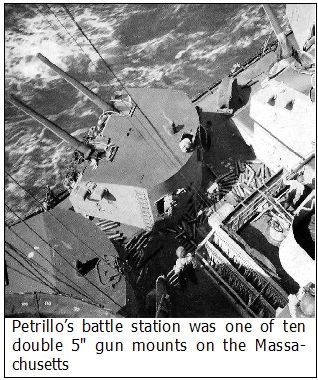

METHUEN – It was late in the summer of 1943 and Tom Petrillo was a shell loader on one of the twenty 5″ guns onboard the battleship USS Massachusetts. After serving 16 months on Big Mamie, and having participated in the invasion of North Africa and later in the support of numerous amphibious landings in the Pacific, Seaman Petrillo was suddenly given one hour to get his things together and ordered back to the states for a new assignment. He would become part of a new Navy program to mix battle-tested sailors with new recruits in an effort to accelerate the training on naval ships about to be launched.

A merchant ship brought Tom back to San Francisco and, after a short leave at home in Methuen, he was ordered to report to Naval Station Bremerton near Seattle for assignment to the USS Midway, an escort aircraft carrier almost finished in the nearby Kaiser Shipyard.

Escort carriers, sometimes called jeep carriers, were smaller, lighter and slower versions of the larger fleet carriers. The escorts were about half the length, one-third the displacement and had about one-third the crew of the larger ships. Each carried only 24-32 fighters and bombers. Amazingly, over 120 of these small carriers were built during the war.

The USS Midway (CVE-63), 512 feet long with a 65-foot beam, was launched on 17 August 1943. She had a top speed of 19 knots and a complement of over 1000 sailors and aviators. Her defensive armament consisted of sixteen 40 mm guns along the sides of the ship and a single 5″ gun on the stern.

The Midway was commissioned on 23 October 1943 at Astoria, Oregon where Tom boarded the ship and set up station in the 5″ gun turret. Unlike the Massachusetts’ armored twin 5″ gun turrets, this 5″ gun was open to the elements and provided minimal protection from enemy fire.

The Midway was commissioned on 23 October 1943 at Astoria, Oregon where Tom boarded the ship and set up station in the 5″ gun turret. Unlike the Massachusetts’ armored twin 5″ gun turrets, this 5″ gun was open to the elements and provided minimal protection from enemy fire.

Shortly after boarding, Tom was promoted from seaman to gunners mate 3rd class.

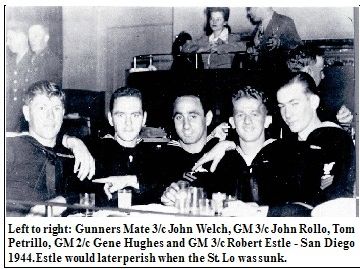

The Midway proceeded south to San Diego to load planes and spare parts for delivery to Pearl Harbor. Tom says every square inch of the flight and hangar decks was loaded with replacement aircraft. Upon return to the states, the Midway picked up another load of aircraft for delivery to Brisbane, Australia.

After one more trip ferrying aircraft, the carrier returned to San Diego where she picked up Air Composite Squadron VC-65 and headed west into the Pacific to fight the Japanese. She joined Admiral Bogan’s Carrier Support Group 1 in June of 1944 for the conquest of the Marianas. During that summer and into the early fall, the Midway participated in strikes against Saipan, Tinian and the invasion of Morotai.

On 3 October the Midway returned to Seeadler Harbor at Manus Island for replenishment. There, the crew learned the name of the ship was going to be changed to the St. Lo to free up the name Midway for a super aircraft carrier then under construction. The new name St. Lo was to commemorate a hard-fought victory by American troops who had liberated the French town on 18 July 1944.

On 3 October the Midway returned to Seeadler Harbor at Manus Island for replenishment. There, the crew learned the name of the ship was going to be changed to the St. Lo to free up the name Midway for a super aircraft carrier then under construction. The new name St. Lo was to commemorate a hard-fought victory by American troops who had liberated the French town on 18 July 1944.

Tom remembers that the crew was quite upset over the name change. Apparently, it is bad luck to have the name of a ship changed while at sea and many on board tried to transfer to other ships. However, because of wartime conditions, that was virtually impossible.

The St. Lo departed Seeadler Harbor on 12 October to participate in the amphibious landings on Leyte in the Philippines. MacArthur landed on October 20th in his famous pledge to return and liberate the islands. The St. Lo provided air support for the invasion forces.

The St. Lo was now part of Rear Admiral C. Sprague’s Task Unit 77.4.3, better known by its radio call sign of Taffy 3. The St. Lo was one of six escort carriers in the task force of 13 ships, which also included a protective screen of three destroyers and four destroyer escorts. From 18 to 24 October the planes of the escort carriers attacked enemy airfields and bases on Leyte, Samar, Cebu, Negros, and Pansy Islands.

On 25 October the task unit was off Samar Island when it launched its initial aircraft strike just before dawn. Shortly afterwards, an anti-submarine patrol plane spotted a large Japanese fleet approaching at high speed from the northwest. At first Admiral Sprague thought the pilot had mistaken U.S. ships for the Japanese, but then lookouts quickly confirmed that they were enemy ships. The surprise attack by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita’s Center Force had taken the Americans completely by surprise.

On 25 October the task unit was off Samar Island when it launched its initial aircraft strike just before dawn. Shortly afterwards, an anti-submarine patrol plane spotted a large Japanese fleet approaching at high speed from the northwest. At first Admiral Sprague thought the pilot had mistaken U.S. ships for the Japanese, but then lookouts quickly confirmed that they were enemy ships. The surprise attack by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita’s Center Force had taken the Americans completely by surprise.

Composed of four battleships, eight cruisers and 12 destroyers, the overwhelming Japanese force was poised for a decisive victory. The largest ship, the 72,000 ton superbattleship Yamato, displaced more tonnage than all 13 American ships combined.

The faster Japanese force closed in and at 0658 opened fire on Taffy 3. What followed next was one of the most heroic naval battles of World War II.

Admiral Sprague immediately ordered the launching of all available aircraft to attack the Japanese fleet with instructions to rearm and refuel at Tacloban airstrip on Leyte to continue the attack. Meanwhile, as Japanese salvos fell around them, the ships of Taffy 3 took evasive action and the destroyers laid down a blanket of smoke to protect the carriers.

Several of the destroyers and destroyer escorts made torpedo runs at Kurita’s fleet and continually harassed the Japanese forces. They would eventually pay a dreadful price. At 0855, the Destroyer USS Hoel, peppered by Japanese shells, was the first to be sunk, losing 267 men in the process. The Destroyers Roberts and Johnston would also be sunk shortly afterwards with the combined loss of another 274 sailors.

The escort carrier Gambier Bay took a shot just below the waterline that knocked out one of her engines and reduced her speed. As she fell behind the others, the Japanese closed in to finish her off. She went down with the loss of another 131 men.

Meanwhile, the planes from Taffy 3 were inflicting considerable damage on the Japanese fleet. U.S. Task Units Taffy 2 and Taffy 3, to the south of the battle, sent additional torpedo planes and dive-bombers. The combined air assault sunk three Japanese heavy cruisers and relentlessly attacked the remaining ships. At about 0930, Admiral Kurita signaled his task force to withdraw, just as two of his heavy cruisers were within a few thousand yards of Taffy 3’s escort carriers. One explanation given later was that Kurita, because of the unexpectedly fierce counterattack by U.S. forces, mistakenly thought he had stumbled upon Admiral Halsey’s entire Third Fleet, and withdrew to fight another day.

Meanwhile, the planes from Taffy 3 were inflicting considerable damage on the Japanese fleet. U.S. Task Units Taffy 2 and Taffy 3, to the south of the battle, sent additional torpedo planes and dive-bombers. The combined air assault sunk three Japanese heavy cruisers and relentlessly attacked the remaining ships. At about 0930, Admiral Kurita signaled his task force to withdraw, just as two of his heavy cruisers were within a few thousand yards of Taffy 3’s escort carriers. One explanation given later was that Kurita, because of the unexpectedly fierce counterattack by U.S. forces, mistakenly thought he had stumbled upon Admiral Halsey’s entire Third Fleet, and withdrew to fight another day.

During all this action, Gun Captain Tom Petrillo was directing fire from the St. Lo’s 5″ gun towards enemy ships. His crew hit one Japanese cruiser three times and left it burning. Another shell from the gun had deflected a torpedo away from the St. Lo’s stern. As the Japanese ships fired their parting shots, Tom’s 5″ gunners scored a direct hit on a retreating destroyer.

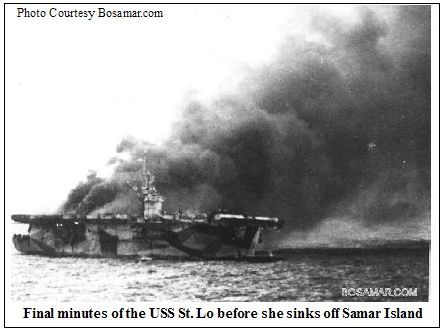

Now the remaining ships of Taffy 3 began to pick up survivors from the water. But the battle wasn’t over yet. At 1050 hours a flight of eight Japanese suicide planes attacked the escort carriers. Three were shot down before they could reach the ships but two of the remaining planes hit the Escort Carriers Kitkun Bay and Kalinin Bay; fortunately, the planes inflicted little damage. A third Kamikaze, with two 500-pound bombs under its wings, crashed onto the flight deck of the St. Lo. At least one of the bombs penetrated to the hangar deck below where crewmen were loading torpedoes and bombs onto returning aircraft. The ordinance exploded, creating a massive gasoline fire which led to additional explosions. The third explosion shook the entire ship and many knew at that point the St. Lo was mortally wounded. The word was passed to abandon ship.

Immediately after the plane hit, burned and injured men started fleeing the hangar deck. On the fantail, Tom Petrillo and two others started assisting the injured and putting life jackets on those that went into the sea. The three stayed behind to help as explosions rocked the structure and they were able to assist 25 to 30 injured sailors get off the ship safely.

The fifth explosion, however, was enormous and close. Tom suffered shrapnel wounds in his right shoulder and left leg and the blast shattered a portion of his hip. Dazed and wounded, he couldn’t get up so he rolled off the deck into the sea below. Once in the water, Tom knew he had to get away from the ship before it went down, but he couldn’t swim because of his injuries. Fortunately, a raft with five men on board came by and picked him up and paddled away from the ship. They also picked up a 17-year-old sailor with his left leg blown off.

Just thirty minutes after the Kamikaze attack, the St. Lo went down. Tom couldn’t watch as it disappeared beneath the surface. The St. Lo became the first U.S. ship to be sunk by Kamikaze attack.

All of Taffy 3’s remaining destroyers and destroyer escorts accelerated their rescue efforts for the many survivors still in the water. The recovery area was large and at one point the ships disappeared from the horizon where Tom and a handful of other survivors were waiting. They felt abandoned. There were sharks in the water that attacked some of the wounded sailors. Hours went by as Tom and the others waited for rescue. Suddenly, late in the day, they saw ships approaching on the horizon. At first they were jubilant, but then someone said they might be Japanese and fear spread throughout the survivors. Fortunately, however, the ships turned out to be Taffy 3’s destroyers coming to the rescue.

Tom was eventually picked up by the Destroyer USS Raymond. As Tom lay in a stretcher on the deck, he will never forget watching the burial at sea of four fellow sailors who died after being brought on board. The captain said a prayer and made a few remarks, the bugler played taps, and the four bodies draped by the Stars and Stripes slipped into the sea. A total of 128 men were lost when the St. Lo went down.

Tom was finally brought below deck where a Navy corpsman administered morphine and marked his forehead. The destroyer headed for Leyte Harbor as Tom slept that night and the next morning he was transferred to a hospital ship. He was still in his wet and oil-soaked clothes when he remembers the doctors and nurses cutting off his uniform and administering anesthesia. When he woke up later, he was in a full body cast from his ankles to his chest. There was also a bar holding his leg casts apart so that his hip could heal in the proper position.

Another hospital ship, the USS Comfort, would eventually take Tom to a field hospital on New Guinea where he spent two months in a Quonset hut. Later on, the SS Lurline, a converted luxury liner, would bring Tom back to San Francisco after picking up additional wounded in Australia. Following a brief stay at the Oakland Naval Hospital, Tom was put on a train to Boston by way of Chicago. Because of the body cast, Tom could not enter the train through the narrow doorway. A window had to be removed and he was passed through it to a special area the train crew had prepared for him. The trip to Boston required three different trains and each time a window had to be removed to transfer him in and out.

On New Year’s day 1945 Tom arrived at South Station in Boston and was taken by ambulance to the Chelsea Naval Hospital. On January 19th he had his third or fourth operation – Tom had lost count at this point. It wasn’t until March that the doctors finally removed his body cast and allowed him to use crutches. On 19 July 1945, Tom Petrillo was discharged simultaneously from the hospital and the Navy. He was judged 60 percent disabled.

Tom returned to Methuen and, after a long recovery period, briefly worked at the Rockingham Race Track followed by the Arlington Shoe Factory. Then he got a job as a carpenter at Hanscom Field in Bedford and would spend the next 20 years helping to maintain the infrastructure of the base. When he retired, he started the Petrillo Construction Company which his son, Kevin, now runs.

In the late 1940s, Tom was filling out some insurance paperwork at the Clover Hill Hospital in Methuen when he met Margarite Fitzpatrick and asked her out to lunch. One thing led to another and the two were married in September of 1949. The Petrillos have four children: Kevin, Carrol, Susan, and Kathleen; 12 grandchildren; and 12 great grandchildren.

Tom Petrillo is a lifetime member of the Disabled American Veterans Post 2 in Lawrence (Methuen) and a member of VFW Post 8546 in Salem, N.H.

Gunners Mate 3/c Tom Petrillo, we thank you for your service to our country.

Final Note: Last summer Tom got a phone call from a former shipmate that he had never spoken with before. It was that of Shipfitter and Seaman 2/c Louis Casiami, the last injured sailor Tom had put a life jacket on and helped over the side on that fateful day in 1944. The sailor and his wife had finally tracked him down after 62 years to personally thank him for what he had done so heroically, so long ago.