By: Ted Tripp – September, 2006

LAWRENCE – In early 1945, Pvt. Eldon Berthiaume of the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division was captured by the Germans in the small village of Utweiler, Germany. He and other Americans taken prisoner were force-marched deeper into Germany and, after a temporary stay at a transitional POW camp, ended up at Stalag VA [5A] in Ludwigsburg.

Stalag VA consisted of wooden barracks surrounded by a perimeter of fences and barbed wire. There were large groups of POWs from Russia, France, Britain, Poland, India and the United States. The roofs of the buildings were marked with KG (for Kriegsgefangener, the German word for POW) and had a large, red cross painted on them so that Allied planes would not attack the prison complex.

There was never enough to eat and Eldon always looked forward to the K-rations delivered occasionally by the International Red Cross. Much of the rest of the time the food consisted of a green soup – nicknamed “spinach soup” – and chunks of lard. When Eldon was eventually liberated, he was about 50 pounds lighter than when he was captured.

Eldon remembers that every day like clockwork the Germans had a ritual where they would parade from the camp hospital – and purposely in front of the American POWs – a wooden box covered by an American flag. He never found out if there was an actual body inside the box or if the Germans were just using the “performance” for psychological reasons.

At the time of Eldon’s imprisonment at Stalag VA, the Allies were quickly closing in on what was left of the German Army. Eldon and the other POWs could see dogfights overhead between the Messerschmitt and American fighters. If an American pilot was shot down and then brought to the camp, the prisoners would press him for the latest news on the war. They wanted to know how close the U.S. Army was to their location. Liberation was always on their minds.

After months at the POW camp, one night Eldon and the others noticed explosions on the distant horizon. The next morning the Germans suddenly moved all the prisoners out of Stalag VA and started marching them even further into Germany. The Russians led the column, as they always would in the days ahead. They marched from sunup to sundown and Eldon remembers how hard it was on some of the older GIs who were in their thirties or forties.

Younger soldiers like himself would help carry on their shoulders the ones who had trouble keeping up. For those who fell and couldn’t rise, the butt of a German rifle was swiftly administered.

At night, the exhausted prisoners had to sleep in the open fields beside the road. It was still cold with snow on the ground from the harsh winter months. The cold made it especially hard to sleep. Eldon remembers one night when he was able to find a large wooden barrel which he shared with another GI to conserve body warmth.

Eldon also recalls a night where the prisoners could hear the drone of Allied bombers flying overhead – and, incredibly, it lasted all night long. The sound was particularly heartening to the prisoners, as it reinforced their hope that it was just a matter of time before the war would soon be over.

Food was always in short supply. Eldon noted that the POWs considered any fresh snails they found along the side of the road as “special treats.” Another source of precious food was the half-rotten apples still hanging on nearby trees from the previous fall season.

During the daytime, the forced march turned out to be especially dangerous. American planes might suddenly appear overhead and strafe the column with machine gun fire. The pilots unfortunately didn’t know that those on the road below were Allied POWs. The prisoners were then caught in a quandary. If they left the road to avoid the strafing – and went too far – the German guards would shoot them. If they stayed on the road, the American planes would kill them. It was always a gamble on what to do.

A section of the march took the prisoners through a small town which had just been bombed by Allied planes. The residents, many injured, were still searching for their relatives and neighbors when the prisoners went by. They yelled and screamed at the Americans as they passed and some spit in disgust towards those they blamed for the destruction.

During the long march, at one point Eldon had a sudden “nature call” and asked a nearby German guard for permission to briefly stop. The guard granted permission and then noticed that Eldon had a rosary draped around his neck. The German, an older man, then pointed to Eldon and asked, “Catholic?” Eldon nodded yes. The guard then pointed at himself and said, “Catholic.” Incredibly, he then proceeded to take out his wallet and show pictures of his family to Eldon. This was one of those rare and short-lived moments when the instinctive “good” of human nature was able to transcend the horrors of wartime.

Late on one of the last days of the march, the Germans let some of the Indian prisoners take a quick bath in a nearby stream. When the Germans ordered them out of the water, three or four just started swimming away. So the German guards shot and killed them. The remaining Indian prisoners then sat down and refused to resume the march until the Indian bodies were recovered and accorded a proper burial on a ceremonial funeral pyre. Amazingly, the Germans relented and that evening the Indian POWs honored their dead comrades.

The delay worked to the advantage of all the prisoners. That same night, after the funeral ceremony, and with the march again underway, the Americans heard machine gun fire in the distance. There was no question that these were American machine guns because of the sharp, crisp, repetitive nature of the noise. The American Army was getting close. Very close.

The delay worked to the advantage of all the prisoners. That same night, after the funeral ceremony, and with the march again underway, the Americans heard machine gun fire in the distance. There was no question that these were American machine guns because of the sharp, crisp, repetitive nature of the noise. The American Army was getting close. Very close.

Only hours later, the Germans unexpectedly separated the Americans from the rest of the prisoners and herded them into a large barn. There were hundreds of exhausted, sick and hungry American prisoners. The Germans left only three or four soldiers behind to guard them.

Somewhere around 6 or 7 a.m. that morning, Eldon and the other American prisoners suddenly heard the rumbling and clinking of tanks approaching. These were the sounds of American tanks. The German guards stood silent. The noise grew louder and then a tank from Patton’s 2nd Armored Division crashed right through the wall of the barn. A GI popped out of the hatch and yelled: “Are there any Americans here!” Eldon remembers a huge roar went up from the prisoners. The few German guards surrendered. The GI in the tank then started throwing out cartons of cigarettes to the crowd and other GIs passed out rifles to the former prisoners.

Soon an Army colonel appeared and said, “My troops are now going after the rest of the prisoners.” But Eldon never found out if the colonel and his men ever caught up and freed the remaining POWs.

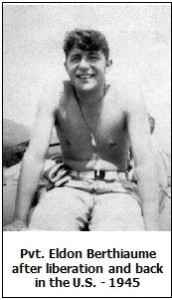

The now-liberated Americans were eventually put onto trucks and taken to an airport where they were flown to Rheims, France, the site of Allied Supreme Headquarters. Here they were deloused, cleaned up and given all the food they wanted. After weeks of rehabilitation, the former POWs were shipped back to the United States. Eldon arrived on U.S. soil in August of 1945 and was granted a 30-day leave to go home to Lawrence.

During Eldon’s capture and imprisonment, the U.S. Army had no idea what had happened to him. All they knew was that he had been missing since sometime in early 1945. When the Army first realized he was missing, it sent a telegram to his parents explaining that Pvt. Eldon Berthiaume was listed as “missing in action,” without further information. When Eldon’s mother, Aldona, got the telegram, she started attending Mass every day praying for her son’s safe return. She didn’t find out that Eldon was actually alive until after he was liberated by Patton’s forces some four months later.

During Eldon’s capture and imprisonment, the U.S. Army had no idea what had happened to him. All they knew was that he had been missing since sometime in early 1945. When the Army first realized he was missing, it sent a telegram to his parents explaining that Pvt. Eldon Berthiaume was listed as “missing in action,” without further information. When Eldon’s mother, Aldona, got the telegram, she started attending Mass every day praying for her son’s safe return. She didn’t find out that Eldon was actually alive until after he was liberated by Patton’s forces some four months later.

When his leave at home was up, Eldon was sent by train to Lake Placid, New York where the Army had a special facility for treatment of returning POWs. Here Eldon recuperated from his ordeal along with many other former American prisoners.

After Lake Placid, Eldon was given orders to report to Ft. McClellan in Anniston, Ala. to become an Army instructor. He would subsequently be promoted to staff sergeant before being discharged from the service in 1946.

Upon returning home, Eldon went back to work at the Shawsheen Mill for several years before eventually taking a job at Western Electric in Lawrence. In 1956 he was transferred to the company’s huge new complex in North Andover on Rte. 125. He worked in various jobs making telephone equipment and ended up as a supervisor in microwave equipment engineering when he retired in 1983.

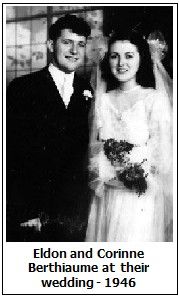

In the summer of 1943, before Eldon entered the service, he had attended a family outing in Canada on Prince Edward Island. Here he met Corinne Gallant and was immediately infatuated with her. While there was little contact between the two during Eldon’s army service, he finally got back in touch with her after the war. In 1946, Corinne and Eldon were married in a Canadian ceremony. This past July 10th, the couple celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary.

In the summer of 1943, before Eldon entered the service, he had attended a family outing in Canada on Prince Edward Island. Here he met Corinne Gallant and was immediately infatuated with her. While there was little contact between the two during Eldon’s army service, he finally got back in touch with her after the war. In 1946, Corinne and Eldon were married in a Canadian ceremony. This past July 10th, the couple celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary.

The Berthiaumes have four daughters, Ruth Messina, Carole Bonin, Elaine Foley and Lisa Singleton; seven grandchildren; and seven great grandchildren.

Eldon is a member of American Legion Post 122 in Methuen and also a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Staff Sergeant Eldon Berthiaume, we thank you for your service to our country and the sacrifices you endured to protect our freedoms.

As a final note, Eldon would like to extend a special thanks to John Doherty, the Director of Veterans’ Services in Andover, who was a tremendous help to him over the past two years in his application for POW benefits.