By: Helen Mooradanian – August, 2011

In May 1944 during World War II, near Carano, Italy, 24-year old Sergeant Van T. Barfoot risked his life in extraordinary heroism. Single-handedly, he killed seven German soldiers, destroyed three machinegun nests, faced down three armored tanks, and captured 17 German prisoners!

In May 1944 during World War II, near Carano, Italy, 24-year old Sergeant Van T. Barfoot risked his life in extraordinary heroism. Single-handedly, he killed seven German soldiers, destroyed three machinegun nests, faced down three armored tanks, and captured 17 German prisoners!

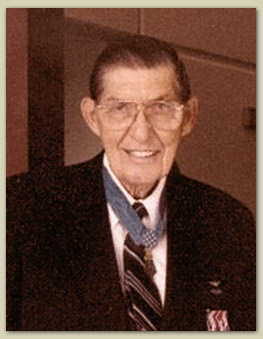

For his valor, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant and awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Today at 92, Barfoot is one of our oldest living Medal of Honor recipients.

Combat service in three wars—World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War—earned him twenty medals including the Silver Star, Bronze Star, and three Purple Hearts.

In December 2009, outside Richmond, Virginia, at the age of 90, Colonel (retired) Barfoot, engaged in warfare of another kind.

This time it required standing fast. He refused to remove the American flag from the 21-foot flagpole he put up in his front yard, on his property. The homeowners’ association harassed him. Their lawyers threatened legal action.

Barfoot stood firm. He would fight them in court.

No surrender.

Where does such courage come from?

Where does such courage come from?

Who is the source of his strength?

When your back is against the wall

Born on June 15, 1919, on a farm in Edinburg, Mississippi, Colonel Barfoot says, “I’m just a country boy who grew up at Rye’s Creek and was very fortunate that God has been very good to me,” he told WLBT-Jacksonville.

In 1940, before the draft, Barfoot enlisted in the U.S. Army and was promoted to Sergeant in December 1941. In 1943 he was reassigned to the 157th Infantry, the 45th Division. He took part in the Allied invasions of Sicily (July 1943), Salerno, Italy (September 1943), and Anzio (late January 1944). At Anzio the 45th Division held off the Germans for four months.

By May 1944, near Carano, they found their backs against the wall.

Before them lay a wheat field, cemetery, and minefield—and the German army.

Behind them stretched the woods, and the Mediterranean.

There was only one way to go. Forward.

Barfoot knew the Germans were laying mines there. Each day, he closely observed them come out, work, and then go back in. By night, he led small patrols, 25 to 30 in all, mentally mapping out where the mines lay.

Barfoot knew the Germans were laying mines there. Each day, he closely observed them come out, work, and then go back in. By night, he led small patrols, 25 to 30 in all, mentally mapping out where the mines lay.

On the morning of May 23, 1944, Barfoot volunteered to lead a squad behind enemy lines, using his information. Early that morning, under cover of a light rain and artillery shelling, they advanced 300 yards beyond the cemetery. Then both the rain and the shelling stopped.

Now visible to the Germans, they were exposed to machinegun fire.

Worse yet, they were completely cut off!

No way to communicate with their commander.

No radio—it had been damaged by machinegun fire.

No runner—he had been wounded before setting off.

No artillery support.

No way to contact the unit on their flank.

Barfoot decided to go off alone. He crawled along the minefield until he came within 20 feet of the first German machinegun nest. He threw a hand grenade, killing two and wounding three Germans.

He kept on going down the trenches to the second German machinegun emplacement. With his tommygun, he killed two more Germans and captured three.

Since he had no way to communicate with his men, he said, he just kept going.

When the third German machinegun crew saw all this, they surrendered to Sergeant Barfoot.

Leaving the prisoners with his squad, Barfoot proceeded to seize more prisoners. In all, he single-handedly captured a total of 17 Germans! In three hours!

Slaying Goliath

Early that afternoon, the Germans launched a fierce counterattack.

Three German Mark VI tanks arrived, a “fortress on wheels” with their 88mm gun and four inches of armor. They aimed straight for Barfoot on patrol with another soldier (he had ordered the others to withdraw to a hill).

Grabbing the soldier’s bazooka, Barfoot ran to an exposed position, directly in their path. From a distance of 75 yards, on his first shot he destroyed the tread of the lead tank, disabling it. As the crew jumped out, Barfoot killed three of them with his tommygun. The other two tanks turned away.

Knowing where the Germans would likely counterattack, Barfoot headed there. Finding an abandoned German fieldpiece on the way, he destroyed it with a demolition charge.

Then although “greatly fatigued by his Herculean efforts,” while returning to his platoon Barfoot helped carry two of his seriously wounded men 1,700 yards (about a mile) to safety.

His Congressional Medal of Honor, presented before his troops near the frontlines in France on September 28, 1944, reads in part, for “extraordinary heroism, magnificent demonstration of valor, and aggressive determination in the face of pointblank fire.”

Spiritual courage: the strength to endure

Asked if he were ever afraid, Barfoot replied, “Why should I fear when I have the Lord? The Lord will look out for me,” daughter Margaret Nicholls told The Valley Patriot.

“My Dad was raised by a very devout Christian mother, and his faith in God has been at the very core of his being since childhood. That’s what gave him courage in battle.

“Throughout the war, he carried the pocket Bible of his wife’s mother, drawing strength from God’s Word, and read the Bible to his men. At each military post, he taught Sunday School.

“To this day, he reads the Bible daily, often three times a day, ” she said.

On his shelves, books by Billy Graham, Oliver North, and Ronald Reagan sit next to histories of World War II.

In warfare, success leads to surprise attacks.

In October 2009, Mississippi designated a portion of Highway 16 as the “Van T. Barfoot Medal of Honor Highway,” beginning from Carthage, Mississippi, where Barfoot had first enlisted in the Army, through Edinburg to the Leake/Neshoba County line.

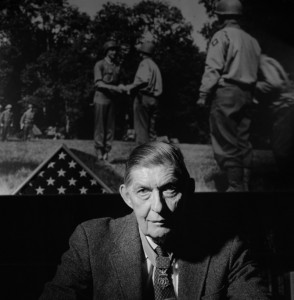

Two months later, in December, his display of the American flag triggered a dispute.

The flagpole was too tall and “not aesthetically appropriate,” the homeowners’ association claimed. It must come down.

Barfoot refused. It was a matter of honor. “The flag should be flown from a height, not half-mast from a porch. It’s not dignified that way.”

The association’s law firm threatened court action.

Barfoot stood firm. “I was raised to respect the flag.” Since his Army days, he has raised the flag each sunrise and lowered it each sunset.

In the uproar that followed, the national media and even U.S. and state senators got involved. The association’s lawyers dropped the charges.

“In the time I have left, I plan to continue to fly the American flag without interference,” Barfoot told the Associated Press.

Barfoot remains humble about his WWII heroism. “People say I did something miraculous. I don’t think so. I don’t think I did any more than any good American would do,” he told Ron Capps (Foreign Policy, 11/11/2010).

But for a grateful nation, the closing words of his Medal of Honor citation say it all, calling his heroism “a perpetual inspiration to his fellow soldiers.”

And to his fellow Americans for generations to come.

Col. Barfoot has always honored God, country, and family.

May his legacy inspire us all to hold fast to this truth, “In God we trust.”

Helen Mooradkanian is former senior editor of a national specialized business magazine and currently a freelance writer and book editor. A Wellesley College graduate, she has a master’s from Fuller Seminary. Email her at: hsmoor@verizon.net

Helen Mooradkanian is former senior editor of a national specialized business magazine and currently a freelance writer and book editor. A Wellesley College graduate, she has a master’s from Fuller Seminary. Email her at: hsmoor@verizon.net