HERO IN OUR MIDST

By: Helen Mooradkanian – September 2013

It was January 1, 1945 as the convoy of 556 ships filled the horizon—LSTs, troop ships, aircraft carriers, submarines, destroyers, cruisers, and warships equipped with the largest guns, 16-inch diameter. They were sailing from Dutch New Guinea to Lingayen Gulf on the island of Luzon, in the Southern Philippines—where the Allied invasion of the Philippines was about to begin. On January 9, General Douglas MacArthur launched the massive land-sea-and-air battle that caught the 287,000 Japanese defenders by surprise. They had not expected the invasion for another few weeks.

Frank Yount, 115th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees), now of North Andover, was in that huge convoy. “We had been building the Navy’s advance base at Hollandia, on Humboldt Bay, in Dutch New Guinea, when we received orders to depart for Lingayen Gulf.

“As we approached Lingayen Gulf, the sky lit up from exploding fire. Aircraft dropping bombs. Navy guns ablaze. Mortar fire. Japanese “kamikaze” suicide bombers diving into our warships.

It was a strategic victory for the U.S. and its allies, one that military historians say no one had anticipated when the U.S. Sixth Army stormed the beaches of Lingayen Gulf on January 9. U.S. troops far outnumbered those used in North Africa, Italy, or southern France. Some 68,000 troops from ten U.S. divisions and five independent regiments made amphibious assault landings and secured a 20-mile beachhead by nightfall. Several hundred thousand more followed.

This decisive victory set the stage for the liberation of Manila and the Philippines. It was due, in part, to the Navy’s advance bases constructed by the Seabees far out into the Southwest Pacific. Without them, combat troops and ships would not have had the vital support services close to their theater of operation.

“As soon as we arrived at Lingayen Gulf on Luzon, January 21, 1945, we began building an airfield for the Marines and roads for heavy vehicles, even while under enemy fire,” Frank said.

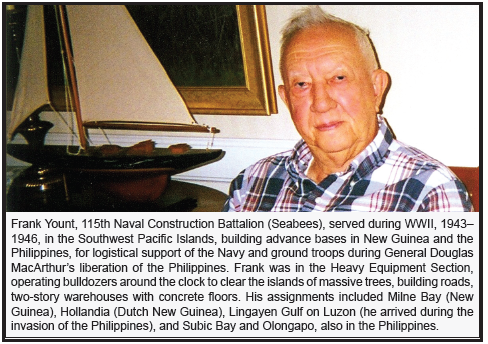

Frank Yount was 17 years old when he left the family farm in rural North Carolina (Granite Falls, population 4,000) to join the Navy. Assigned to the 115th Seabee Battalion, heavy equipment section, he helped build naval advance bases to support combat troops in the New Guinea and Philippine campaigns, and also the planned assault on the Japanese mainland. The 115th Seabees went in and cleared the land, built roads and huge parts depots, constructed airstrips and landing fields, staging areas for troops, and repair and refueling bases for ships.

“I had never seen a bulldozer until I joined the Navy,” says Frank. Yet the first time he saw one, during training at Davisville, RI, he climbed up into the cab and began test driving it. Very quickly he was charged with training others. At the age of 17, he became captain of the bulldozer squad.

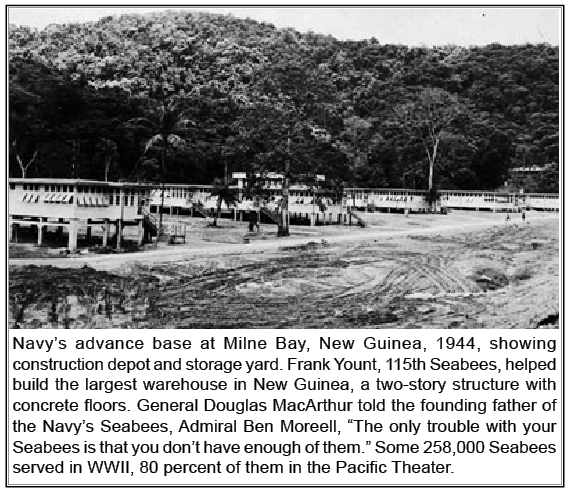

Milne Bay, New Guinea

On December 10, 1943, Frank Yount had departed from Davisville, RI, on an old cargo vessel, “The Alcoa Patriot,” along with 1600 other Navy Seabees. Destination: Milne Bay, on the southeastern point of Papua New Guinea, in the Southwest Pacific.

The 69-day voyage was slow and torturous, at 6 knots an hour (about 7 miles). No escort. Buffeted by wild Atlantic storms. German subs off the coast of Cuba in the Caribbean. “Before we reached the Panama Canal, we were held up five times while U.S. destroyers from the naval base at Guantanamo Bay chased off the enemy subs.”

When they finally debarked at Gamadodo (Frank was the first to go ashore with his bulldozer), they “battled a sea of knee-deep mud…torrential downpours that never let up… thick clouds of mosquitoes (it’s one of the worst malaria spots in the world)…jungle rot that literally dissolved our boots…and the occasional python that slithered across our path…

“We operated those bulldozers seven days a week, around the clock, and cleared several hundred acres of jungle. We uprooted and knocked down gigantic trees, built sawmills and parts depots, ammunition magazines (storage). We pushed aside layers of mud, hauled coral from the beach, crushed and surfaced it, added gravel 2-feet thick in order to build and grade roads. We built airfields and landing strips, adding an additional sub-layer of interlocking metal plates, each 12 feet long, pouring concrete over them.”

Milne Bay’s harbor stretched along 20 miles of coral and mud beaches that turned into dense, swampy jungles extending all the way to the mountains. Given a tropical rainfall of 125 inches a year and muddy, sandy soil, it was hardly suitable for heavy construction. Yet the Seabees did the impossible.

“Before we left, we had built a huge replacement center that became one of the principle staging areas for the transfer of Army, Navy, and Marine troops in the New Guinea and Philippine campaigns. By mid-1944, we had put up barracks for housing 40,000 men. We also built a huge two-story, 120,000-square-foot spare-parts warehouse, with concrete floors—probably the largest building in New Guinea—that stored everything from ships’ engines to the smallest warship components.” Other structures included a pontoon assembly depot, and staging area where ships could anchor, refuel, and be refitted.

After completing their assignment at Milne Bay, the 115th Seabees boarded LSTs on December 1, 1944, and departed, in a five-ship flotilla, up the northeast coast of New Guinea to another advance base, Hollandia, on Humboldt Bay in Dutch New Guinea, arriving there December 18. Hollandia became the advance headquarters of the Seventh Fleet, a logistics base for the Navy, as well as a supply base for General MacArthur during the liberation of the Philippines.

Preparing for assault on Japan

Preparing for assault on Japan

On February 8, 1945, the 115th became the first Seabees to debark at Subic Bay naval base on the west coast of Luzon, to prepare the base for the planned invasion of Japan. “At Subic Bay, we constructed facilities and camps, a pontoon pier, and docks. We also rebuilt the adjoining small naval base at Olongapo, which the Japanese had completely destroyed a few days before the U.S. invasion, systematically burning down churches, homes, buildings, and breaching the dike to flood the lowlands. We constructed new facilities for port director, communications, repair base for destroyers and submarines, dispensary, and housing for 1200 men in 32 two-story Quonset huts. We built roads, six steel warehouses (160 by 200 feet), and supervised completion of an amphibious training center where Army and Marines could practice all stages of assault landings on beaches.

Built on rock—or sinking sand?

After Japan surrendered, they remained in Luzon for a few months and built roads through the mountains for the Filipinos, hauling rocks from streambeds and crushing them. As a civil engineer and former operating manager of a sand and gravel company, Frank Yount knows the importance of building on rock, not sinking sand.

Jesus also talked about building. “Anyone who listens to My teaching and obeys Me is wise, like a person who builds a house on solid rock. Though the rain comes in torrents and the floodwaters rise and the winds beat against that house, it won’t collapse, because it is built on rock. But anyone who hears My teaching and ignores it is foolish, like a person who builds a house on sand. When the rains and floods come and the winds beat against that house, it will fall with a mighty crash” (Matthew 7:24-27).

Helen Mooradkanian is our Valley Patriot Hero columnist and a former business writer. She is also a member of the Merrimack Valley Tea Party, You can email Helen at hsmoor@verizon.net

Helen Mooradkanian is our Valley Patriot Hero columnist and a former business writer. She is also a member of the Merrimack Valley Tea Party, You can email Helen at hsmoor@verizon.net