By: Helen Mooradkanian – March 2013

Having arrived in France only in mid-November, they were somewhat inexperienced. Auffay, Luneville, Bining, and Rohrback did not really prepare them for the nightmare of Herrlisheim. Herrlisheim became their “baptism by fire.” It was there that they lived up to their name, the “Hellcats” Division.

Snow 15 inches deep and heavy ground fog blanketed the region around the Rhine River. As Paul’s battalion moved across the flat, open field, they advanced directly into the line of heavy machine gun fire. They had entered “a perfect kill zone.” No place for concealment.

The canals were swollen with ice and snow and all but one bridge had been destroyed. The Germans lay hidden behind the small clusters of woods and railroad embankments, along with major elements of the 10th SS Panzer Division—including a tank brigade with 88mm and 75mm guns, a mortar company, motorized infantry brigade and anti-tank guns. Not only did the Germans far outnumber the Americans they also had more combat experience. Their Mountain Division had just returned from Norway.

More than half the Americans in one company were killed in the first five minutes. The rest were pinned to the ground by the very intense fire, unable to move. Tracers “zinged” above them “like strings of angry bees.” Some 35 men survived, including the wounded. The Germans were amazed any were still alive. They called the Twelfth the “Suicide Division.” By 10 a.m., Paul’s battalion had lost all radio contact with their division’s 43rd Tank Battalion, which was to have come to their aid. Despite repeated calls for reinforcements, no help came. Only silence. Then from the top came the command, “No retreat.”

Around 4 p.m., six Panther tanks that could maneuver over rough terrain, with their deadly long-range 75mm guns, attacked the flank of Paul’s company. There was still no trace of the 43rd Tank Battalion. “Darkness fell. Throughout the night we continued fighting in hand-to-hand combat. At midnight, the Germans launched a large-scale infantry attack that never let up. Their heaviest assault came at 4 a.m. In the Germans’ final push, about 140 Americans escaped across the Zorn River. The Germans infiltrated among our platoon positions, their white capes camouflaging them in the snow and fog.

“At dawn on January 18, there was still no word on the 43rd Tank Battalion. The one building we were using as a command post had exploded in flames. German tanks had blasted through our command post twice. Our platoon positions had all been overrun. We had nothing left to fight with. We were forced to surrender.” Later it was reported that most of the 43rd’s Sherman tanks had been destroyed or heavily damaged. “Bloody Herrlisheim” was indeed a nightmare.

Paul was in a group of 35 Americans captured together at Herrlisheim on January 18. He and his unit marched on foot from the Rhine through Baden-Baden and on to Stalag 5A at Ludwigsberg, near Stuttgart. There he was imprisoned for 10 days in a former cavalry stable, virtually unheated. “I remember being cold all the time. There were 350 of us in the American barracks, sleeping in tiered bunks with straw ticking—and no blankets. Toilet facilities were poor. We were covered with lice but received only two delousing’s. Since we had only the clothes on our backs, we were not able to wash them in the frigid temperatures.” After 10 days, they were transported in unheated boxcars for four days, with minimal food and water, to Stalag 11B at Fallingsbostel, 30 miles from Hanover. Temperatures at night fell between zero and 15 degrees. Everyone suffered badly from frostbite.

Paul remained at Stalag 11B for two and one-half months. It had about six barbed-wire compounds covering probably 10 acres of farmland. Guard towers could sweep the entire area in machine gun fire. “We were always cold—and hungry. Temperatures dropped to around zero at night. A single blanket covered the lice-ridden straw mattress. We had virtually no heat. Our feet were frostbitten.

“But worst of all was the constant hunger. It tormented us day and night. We thought of nothing but food. We talked of nothing but food. Literally. Each day we were allowed a meager piece of ersatz black “bread”—a poor imitation of the real thing. Daily rations also included a cup of rutabaga soup which literally tore out your insides, 3 or 4 ounces of potatoes, a cup of barley water, occasionally a piece of so-called margarine, actually lard. Twice we had horsemeat. In three months, I lost 20 lb. My bunkmate, who was much heavier, lost 40 lb. We used cigarettes to barter for everything, from food and pens to clothing. Twenty cigarettes could buy a loaf of bread from a German guard.

“But worst of all was the constant hunger. It tormented us day and night. We thought of nothing but food. We talked of nothing but food. Literally. Each day we were allowed a meager piece of ersatz black “bread”—a poor imitation of the real thing. Daily rations also included a cup of rutabaga soup which literally tore out your insides, 3 or 4 ounces of potatoes, a cup of barley water, occasionally a piece of so-called margarine, actually lard. Twice we had horsemeat. In three months, I lost 20 lb. My bunkmate, who was much heavier, lost 40 lb. We used cigarettes to barter for everything, from food and pens to clothing. Twenty cigarettes could buy a loaf of bread from a German guard.

“Occasionally we were given a Red Cross package to share four-ways. We Americans would share our meager rations with the Russian POWs whom the Germans hated and mistreated, denying them food and medical care until they all died of starvation and disease. “I had an acute case of jaundice but lay helpless for three days in my bunk since only severe cases, like pneumonia were transferred to the clinic. A British medical doctor, a POW for five years who had fought in North Africa, did a great job for us with the limited supplies he had (paper bandages and whatever he could get through the Red Cross). “We were never tortured or beaten but I did witness the German guards repeatedly beating the Russian POWs, for whom they had a long-standing hatred. They were quite open about it.”

British “Desert Rats” liberate us

Finally the captives were set free! “On April 16, 1945, the British 7th Armored Division—the famed “Desert Rats” who had fought in North Africa and in most of the major campaigns in WWII—stormed in and liberated us! On April 26 we left Stalag 11B, were flown to Oxford, England, and the 318th Hospital. On June 3, 1945, I boarded the SS Tarleton Brown for the United States.”

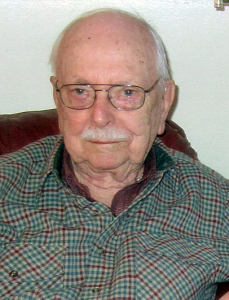

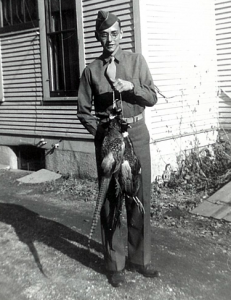

An emotional reunion took place when Paul Stillwell arrived home in Virginia, Minnesota on June 27, 1945. His father, a minister who had served in Congregational and Episcopalian churches in Illinois, Minnesota and South Dakota, had written to Paul several times a week, letters that could never be delivered. Although they had no chance for communication during his imprisonment, he says, “My dad told me he never stopped praying for my safe return.

He knew—he had a peaceful assurance deep in his heart—that the Lord would bring me home safely.” Fervent prayers and the power of a father’s love. It was the Father’s love that sent Jesus to the cross to open wide the prison doors and set the captives free. Jesus said, “He has sent Me to heal the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives…to set at liberty those who are oppressed [bruised, crushed in spirit]” (Luke 4:18).

Helen Mooradkanian is our Valley Patriot Hero columnist and a former business writer. She is also a member of the Merrimack Valley Tea Party, You can email Helen at hsmoor@verizon.net

Helen Mooradkanian is our Valley Patriot Hero columnist and a former business writer. She is also a member of the Merrimack Valley Tea Party, You can email Helen at hsmoor@verizon.net