By: Charles Ormsby – September, 2005

By: Charles Ormsby – September, 2005

NORTH ANDOVER – Alexander Milne rarely speaks of his wartime experiences, even with fellow veterans. Such conversations were uncommon even with his brother, Donald, who served on the Battleship Texas at Normandy, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and who passed away two years ago. Alex found it difficult to explain the reluctance veterans have when it comes to recalling their experiences in the war. Maybe it is modesty. Maybe it’s the painful memories of the suffering and of the loss of their fallen comrades. In any case, it is just difficult.

Alex, currently a resident of Andover, was born in Fall River, Massachusetts in 1925 and graduated from North Andover’s Johnson High School in 1943, just shy of his 18th birthday. In December 1941, when Alex was a junior and only 16 years old, Brockleman’s Market on the corner of Essex and Lawrence Streets burned down. The next morning Alex and his boyhood friend, Bill McEvoy (a current and well-known resident of North Andover), walked to the scene of the fire to see what remained. On their way home, a car pulled up and the driver shouted out, “The Japanese have bombed Pearl Harbor!”

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Donald, who was a year older than Alex, enlisted in the Navy and began his WW II service. After graduation in 1943, Alex turned 18 and registered for the draft. He was notified in September to report to the Army, which immediately sent him to basic training at Camp Perry, Ohio. After basic training and several months at the Rossford and Camp Flora Ordinance Depots, he was shipped to Texas for training in preparation for infantry replacement deployment.

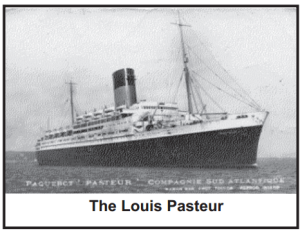

Alex was lucky when it came to berth assignments for the “cruise” to Liverpool, England. He left from the Port Authority docks in New York on an upperdeck berth on the cruise ship Louis Pasteur, a ship that had been designed to be a high-speed civilian ocean liner. The war changed that and, on the ship’s maiden voyage, it was used to save France’s gold reserves – all 213 tons – by transporting them to Canada.

Alex was lucky when it came to berth assignments for the “cruise” to Liverpool, England. He left from the Port Authority docks in New York on an upperdeck berth on the cruise ship Louis Pasteur, a ship that had been designed to be a high-speed civilian ocean liner. The war changed that and, on the ship’s maiden voyage, it was used to save France’s gold reserves – all 213 tons – by transporting them to Canada.

After arrival and for the next week or so, no two nights were spent in the same place. From the Louis Pasteur, Alex went by train to spend a night on a floating dock in South Hampton harbor. Then several smaller ships transported Alex and his fellow soldiers to the port of La Havre, France to spend a night in a “tent City” on a hill outside the port. The next morning they were loaded in “40 or 8” boxcars – a WW I term for boxcars that could accommodate forty men or eight horses – and they were on their way to Belgium. The trip to Belgium was less than first class – let’s just say there were no “facilities”, dining or otherwise, in the boxcar.

Belgium was the gathering point for replacement troops for Allied forces fighting the Germans. Alex spent one night in a huge mill building in Belgium with approximately 1000 other soldiers awaiting orders. He didn’t have to wait long. The next morning Alex and two others were assigned to the 1st Army Group, 69th Infantry Division, 271st Infantry Regiment, Company C.

Once assigned to the 271st, Alex proceeded immediately to the Battle of the Hurtgen Forest, one of the bloodiest and most costly battles fought in U.S. history. Conservative estimates list U.S. casualties at over 24,000 killed with 9,000 more lost to trench foot, disease and combat exhaustion.

Alex joined the battle of Hurtgen Forest after the Allies were in the process of slowly pushing the Germans out.

Alex remembers the Hurtgen Forest as a dark and frigid place with nothing but dirt logging roads and constant shelling by the Germans using 88mm artillery. Shells would hit the tops of trees and then ricochet, explode and rain shrapnel down on the American positions. “They knew where we were” Alex said, “and the German 88s were the most perfect weapons of WW II. They could be used for anti-air operations, artillery, or leveled and used like massive rifles.”

Alex remembers the Hurtgen Forest as a dark and frigid place with nothing but dirt logging roads and constant shelling by the Germans using 88mm artillery. Shells would hit the tops of trees and then ricochet, explode and rain shrapnel down on the American positions. “They knew where we were” Alex said, “and the German 88s were the most perfect weapons of WW II. They could be used for anti-air operations, artillery, or leveled and used like massive rifles.”

Stephen E. Ambrose, in his book Citizen Soldier, described the battle as being “fought under conditions as bad as American soldiers ever had to face, even including the Wilderness and the Meuse-Argonne. Sgt. George Morgan of the 4th Division described it: ‘The forest was a helluva eerie place to fight. You can’t get protection. You can’t see. You can’t get fields of fire. Artillery slashes the trees like a scythe. Everything is tangled.

You can scarcely walk. Everybody is cold and wet, and the mixture of cold rain and sleet keeps falling.’ Troops more than a few feet apart couldn’t see each other. There were no clearings, only narrow firebreaks and trails. Maps were almost useless. When the Germans, secure in their bunkers, saw the GIs coming forward, they called down presighted artillery fire, using shells with fuses designed to explode on contact with the treetops. When men dove to the ground for cover, as they had been trained to do and as instinct dictated, they exposed themselves to a rain of hot metal and wood splinters.”

Alex described the living conditions during this period: they were worse than deplorable. It was one of the coldest German winters on record. Troops slept on the ground amidst 4 or 5 inches of snow. They had no tents or sleeping bags … only their ponchos to wrap around themselves. Men woke up so cold they couldn’t move. Those who were up had to lift their comrades and get them standing by a tree to slowly gain the ability to move. No smoke meant no fires and no hot coffee or hot meals … just cold C-rations. Even with these memories, Alex thinks the weeks preceding his arrival were even worse and the troops suffering even more intense.

While occasionally a “lunch truck” would happen by, cold C-rations were the norm during meal breaks. The frontline troops didn’t even carry mess kits — one badly packed mess kit could rattle and threaten the security of an entire squad or company.

The reader may not fully appreciate the incredible casualties taken by U.S. Forces in the Hurtgen Forest … especially during the battle’s early stages. As noted above, Alex was one of the “replacement infantry.” There were many such replacements. Why? Here is a very short excerpt from the history of 271st commenting on the casualty rates during the period just before Alex’s arrival at the front:

“Replacements flowed in to compensate for the losses but the Hurtgen’s voracious appetite for casualties was greater than the army’s ability to provide new troops.” Lieutenant Wilson recorded his company’s losses at 167 percent for enlisted men.

“We had started with a full company of about 162 men and had lost about 287.” Sgt. Mack Morris was there with the 4th and reported: “Hurtgen had its fire-breaks, only wide enough to allow two jeeps to pass, and they were mined and interdicted by machine-gun fire. There was a mine every eight paces for three miles. Hurtgen’s roads were blocked. The Germans cut roadblocks from trees. They cut them down so they interlocked as they fell. Then they mined and booby-trapped them. Finally they registered their artillery on them, and the mortars, and at the sound of men clearing them, they opened fire.”

When Alex’s unit finally exited the forest, it was a godsend. Finally: rolling hills, flatlands, and fields.

When Alex’s unit finally exited the forest, it was a godsend. Finally: rolling hills, flatlands, and fields.

Here Alex had the luxury of spending one night in a farmhouse. You can detect the relief in his voice as he describes the immense pleasure of spending one night indoors … even if it was with twenty other soldiers in cramped quarters and on the floor. Alex remembers the pleasure of washing his hands in the sink, “It wasn’t a bath but it still felt awfully good!”

Most of the action during this period was not close combat. The threats were from constant shelling by artillery, and numerous mines and booby-traps set by withdrawing German troops. The Germans would set their mines and booby-traps and register their artillery – as described above – and then stand off 5 to 10 miles and shell the American troops as they moved into the new areas. When artillery shells were incoming, which happened ten or twelve times a day, troops would dive for cover before moving out again.

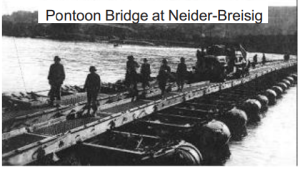

Crossing the Rhine River was a major milestone for U.S. troops. Alex crossed the Rhine at a town called Neider-Breisig – not far from the famous Remagen Bridge where the first Allied crossing took place. Alex and his regiment spent several days helping the Corps of Engineers as they built a pontoon bridge. Alex remembers loosening his jacket filled with numerous heavy objects before crossing over … he didn’t need to be weighted down if the bridge collapsed or the truck went over the edge. The other major milestone for Alex at Neider-Breisig was taking a shower … his first shower since leaving New York 6 weeks earlier!

On April 15, 1945, Alex had a very close call. Just before nightfall his squad was ordered to cross an open field. Suddenly, “the sky lit up like Fenway Park.” Artillery shells timed to explode a hundred or so feet above the ground started going off everywhere. The entire squad turned and raced for cover. Alex jokes that he thinks he passed everyone as he ran from the field. But this was just a preview of coming events.

The next day, Alex was riding on a tank when artillery shells started to rain down on his convoy. Everyone jumped into the nearest gully. Initially, Alex was in the ditch with a medic but the medic soon left to attend a wounded soldier. Shortly thereafter a shell landed about 12 feet from Alex and about 5 feet above him. Shrapnel tore into his neck, shoulder, left leg, and back… one piece lodged in his lung.

The concussion from the shell was so intense that Alex only remembers bits and pieces of what happened next. He vaguely remembers that the medic returned to help stabilize him – probably leaving Alex earlier saved the medic’s life, since the medic had been positioned even closer to the point of impact than was Alex. Soon, Alex was placed on the hood of a jeep and rushed to a field hospital.

Alex spent fourteen months in hospitals before he was well enough to be released. He had to constantly fight infections while recovering from major operations. At one point, about the time his family was first able to visit him, Alex’s weight had dropped to 99 pounds. Twenty-year-old Pfc. Alex Milne was finally released and discharged on June 28, 1946. He still carries shrapnel from that artillery shell in his neck.

Alex worked for the Davis & Furber Textile Company in North Andover for ten years, then with the Andover branch of McCartney’s Clothing store for another 27 years. He lived in North Andover until 1953 when he moved to Andover. Alex and his wife Mary have four sons: Alex, Robert, David, and Gary who all still live in Massachusetts.

Alex worked for the Davis & Furber Textile Company in North Andover for ten years, then with the Andover branch of McCartney’s Clothing store for another 27 years. He lived in North Andover until 1953 when he moved to Andover. Alex and his wife Mary have four sons: Alex, Robert, David, and Gary who all still live in Massachusetts.

Alex Milne, thank you for your service and the sacrifices you made for our freedoms.

Alex Milne was awarded the Combat Infantry Badge, the Bronze Star, the Purple Heart, the European Theater of Operations Medal with Two Stars, the Victory Medal, the American Defense Medal, the Good Conduct Ribbon, and the Sharpshooters Award.