VALLEY PATRIOT OF THE MONTH

By: Helen Mooradkanian – January, 2014

NORTHANDOVER – “We were the second largest convoy to leave for Europe—5,000 of us aboard the U.S. Army troopship George Washington—when we left New York in early 1944, bound for Liverpool, England. By the time we arrived in England in April, two months before the D-Day invasion of June 6, our ranks had swelled enormously,” recalls Sergeant Charles P. Sarantos, 112th Allied Airborne division, then an 18-year old Lowell native who now lives in North Andover.

“On the way, we were attacked by a fleet of German warships, submarines, and aircraft. The cannons’ deep boom reverberated non-stop. Bombs exploded. Ships caught fire. We rescued a great many survivors from the ocean, bringing them on board our ship.” Charlie still remembers the thunderous booming of cannon that resonated deep in the bowels of the ship’s galley, where he was on duty slicing huge slabs of bacon during that long voyage. His unit had been assigned to KP duty.

Once he reached England, Charlie advanced across Europe serving in five major campaigns of WWII. The 112th Allied Airborne Division—comprised of Americans, British, and French—saw combat at Rome-Arno in Italy… in southern France—where they repelled the German counteroffensive in the Battle of the Bulge (December 1944-January 1945) and Operation “Varsity” in March 1945…then advanced through the Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe, and ultimately reached Berlin.

First assigned to the 512th Airborne Signal Corps, which later became part of the 112th Signal Battalion (Special Operations) (Airborne) and the 112th Allied Airborne Division, Charlie set up critical communications networks, working with the American Waco CG-4A combat gliders that had been introduced in February 1941 to transport troops and equipment. Behind enemy lines. In stealth. Under cover of darkness. To shock and confuse the enemy.

First assigned to the 512th Airborne Signal Corps, which later became part of the 112th Signal Battalion (Special Operations) (Airborne) and the 112th Allied Airborne Division, Charlie set up critical communications networks, working with the American Waco CG-4A combat gliders that had been introduced in February 1941 to transport troops and equipment. Behind enemy lines. In stealth. Under cover of darkness. To shock and confuse the enemy.

American combat gliders were shipped, unassembled, in huge wooden crates by cargo vessels to England, where they were assembled and then flight-tested. A single CG-4A glider required five enormous crates. In Manchester, England, Charlie saw them being assembled by untrained British civilians before the Ninth Air Force took over their assembly.

These gliders were towed across the skies by C-47 military transports, and relied on two-way radios to communicate with the C-47 pilot. Charlie set up the communications system, including a 10-volt generator on a trailer loaded into the glider. He also reinforced the CG-4A’s honeycombed plywood floors to prevent heavy equipment from crashing through (which sometimes happened).

Charlie remembers seeing American glider pilots being trained in England. Many were civilians with only a pilot’s license who had been allowed to volunteer because of the shortage of trained operators.

Germany had been effectively using gliders in WWII since 1940 and by 1941 had 300,000 trained glider pilots, produced by their numerous national glider clubs. Great Britain began their program in 1940, followed by the U.S. in 1941 after entering the war.

Four American glider missions flew as part of the D-Day invasion of Normandy, two with extensive fighter escort, although Charlie’s unit was not involved. His unit did see their first action on August 15, 1944, when their combat gliders infiltrated France in Operation “Dragoon,” dropping troops and equipment near Le Muy, France. After setting up a command post there, five days later they moved the post to Valescure, France, to support combat teams attacking a front along the northeast from the northernmost end to the Mediterranean coast 20 kilometers south.

Charlie himself flew on a number of glider missions to test the effectiveness of the radio communications. He had many close brushes with death, more than he wishes to recall.

Yet always, always, underneath he sensed the everlasting arms of the eternal God.

GLIDERS: “FLYING COFFINS”

These combat gliders were dubbed “silent wings” or, more aptly, “flying coffins.” A 300-foot long nylon rope, about 1-inch in diameter, attached the glider to the C-47’s tail via a D-ring coupler. Once they approached the drop zone, the glider was released to float silently to the ground with its cargo of troops and equipment.

The pilot had virtually no control over where he landed. No engine. No propeller. No weapons. In the midst of combat, the gliders were targets before they even landed, so a fast descent was crucial, preferably from altitudes as low as 400 to 600 feet. When under enemy fire, they had to crash-land in trees or other obstacles set up by the Germans. The pilot had only seconds to zero in on his landing spot.

As General William Westmoreland, U.S. Army, Retired, said, “Every landing was a genuine do-or-die situation…They were the only aviators during WWII who had no motors, no parachutes, and no second chances.”

The CG-4A glider could carry a load of more than 4,000 pounds—the pilot and co-pilot plus 13 troops, or various combinations of troops with a jeep, or a 75mm howitzer along with 18 rounds of ammunition and gun crew, or a 1/4-ton truck, or a small bulldozer, as well as ammunition and other supplies. They provided backup for the paratroopers who had arrived earlier.

As the Americans advanced toward Berlin, wire and radio communications became extremely difficult as the supported combat teams moved rapidly over mountains in southern France. Charlie’s unit commandeered the local wire networks to support the forward teams, some as far as 100 miles from the command post. They not only set up direct lines from the command post to each team but they also installed lines between the teams and provided teletype and wire communications to the Sixth Army Group Headquarters.

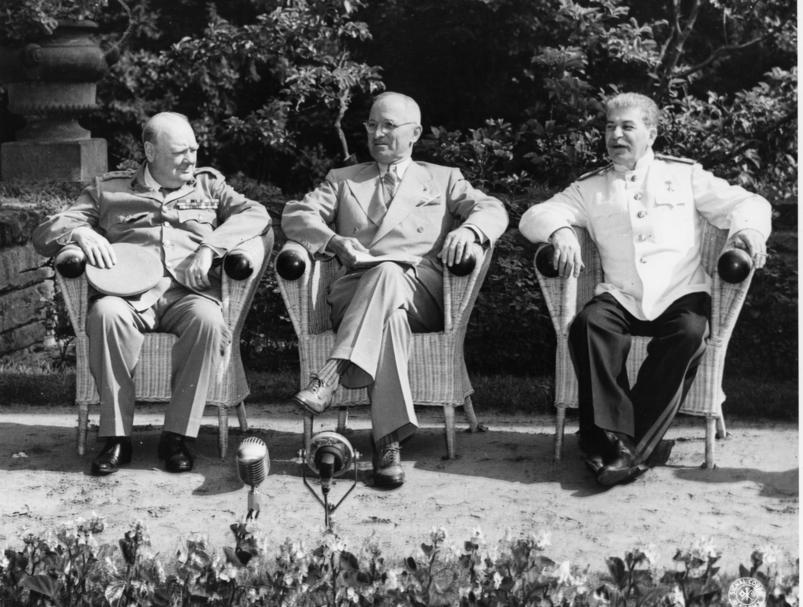

“BIG THREE” Postdam Conference

“BIG THREE” Postdam Conference

With Germany’s unconditional surrender, Charlie, as part of the 112th Army Airborne Signal Battalion, was with the first American troops that entered Berlin for the Allied occupation of that city. The Brandenburg Gate insignia indicates their service in Berlin.

There in Berlin Charlie was present at an historic event that climaxed the end of WWII: the Potsdam Conference, July 16–August 2, 1945, that brought together the “Big Three” heads of state—U.S. President Harry Truman, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin. Charlie was assigned to set up and work communications during the conference, sending and receiving messages, because of his expertise in electronics and his seniority in the military.

At Potsdam, the “Big Three” discussed post-war arrangements in Europe and the portioning of the postwar world. One result was a joint proclamation by the U.S., Great Britain, and China that mandated the terms of Japan’s surrender, ending with the ultimatum that Japan must immediately agree to unconditionally surrender, or else face “prompt and utter destruction.”

“ON A WING AND A PRAYER”

Charlie grew up in a Christian family committed to God and to prayer. “We lived next door to the Greek Orthodox Church, and I literally spent most of my growing up years in the church. I believe in God. I believe in the power of prayer. During the war, I had many close calls with death but I survived miraculously. I always felt God’s protection during the war, and I still feel His protection to this day. I know God answers prayer. He has blessed me abundantly.”

The psalmist wrote, “The Lord is my rock and my fortress and my deliverer; my God, my strength, in whom I will trust…I will call upon the Lord, who is worthy to be praised, so shall I be saved from my enemies” (Psalm 18:2-3).

Helen Mooradkanian is our Valley Patriot Hero columnist and a former business writer. She is also a member of the Merrimack Valley Tea Party, You can email Helen at hsmoor@verizon.net

Helen Mooradkanian is our Valley Patriot Hero columnist and a former business writer. She is also a member of the Merrimack Valley Tea Party, You can email Helen at hsmoor@verizon.net